Dating the origins of persistent oak shrubfields in northern New Mexico using soil charcoal and dendrochronology

Abstract

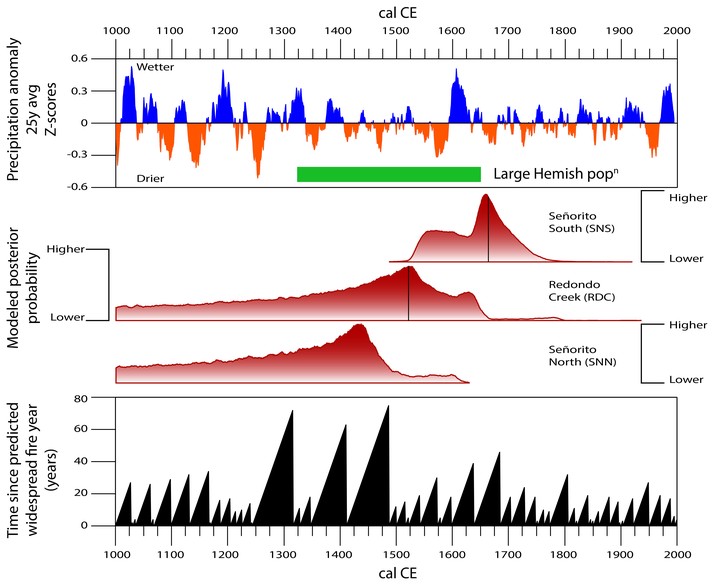

Megafires in dry conifer forests of the Southwest US are driving transitions to alternative vegetative states, including extensive shrubfields dominated by Gambel oak (Quercus gambelii). Recent tree-ring research on oak shrubfields that predate the 20th century suggests that these are not a seral stage of conifer succession but are enduring stable states that can persist for centuries. Here we combine soil charcoal radiocarbon dating with tree-ring evidence to refine the fire origin dates for three oak shrubfields (<300 ha) in the Jemez Mountains of northern New Mexico and test three hypotheses that shrubfields were established by tree-killing fires caused by (1) megadrought; (2) forest infilling associated with decadal-scale climate influences on fire spread; or (3) anthropogenic interruptions of fire spread. Integrated tree-ring and radiocarbon evidence indicate that one shrubfield established in 1664 CE, another in 1522 CE, and the third long predated the oldest tree-ring evidence, establishing sometime prior to 1500 CE. Although megadrought alone was insufficient to drive the transitions to shrub-dominated states, a combination of drought and anthropogenic impacts on fire spread may account for the origins of all three shrub patches. Our study shows that these shrubfields can persist >500 years, meaning modern forest-shrub conversion of patches as large as >10,000 ha will likely persist for centuries.